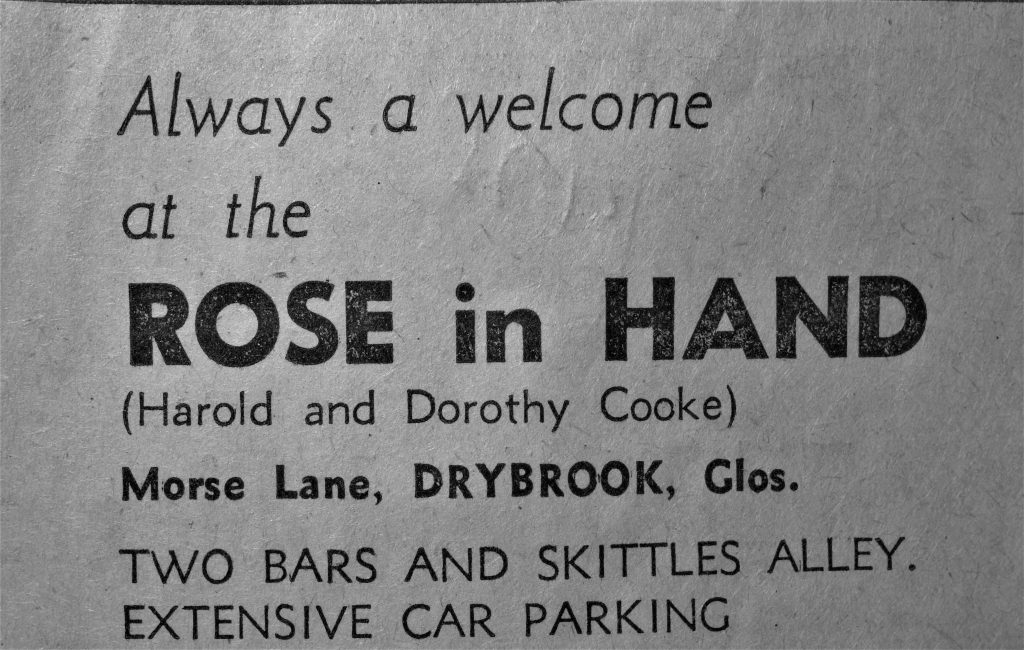

Rose in Hand, Morse Lane GL17 9BE

The Rose in Hand is first referred to in 1823 although an earlier reference simply calls the pub ‘the house’. The pub, only recently closed, was a true, yet somewhat surprising, survivor given its isolated location in an unclassified lane to the west of Drybrook. It was very much a locals’ pub.

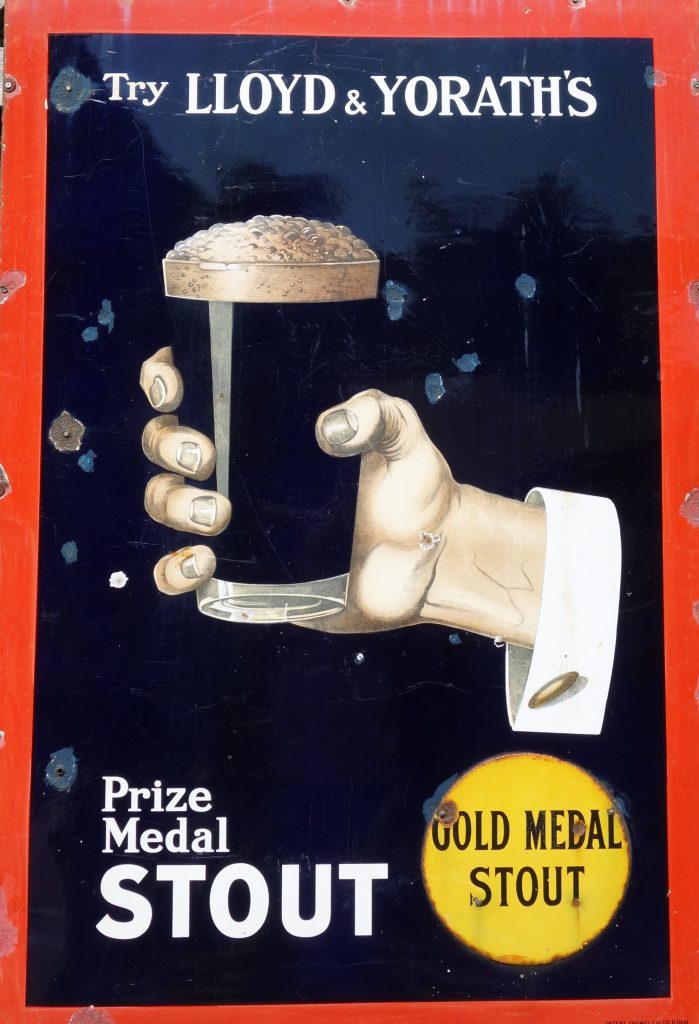

The licensing book of 1903, detailing all the beer houses, alehouses etc in Gloucestershire, give reference to the owners of the Rose in Hand in Drybrook as ‘Lloyd & Co.’ Although not confirmed this is presumably Lloyd & Yorath, brewers at the Cambrian Brewery in Newport, Wales. The rateable value of the alehouse was £13.10s.0d. and the Rose and Hand closed at 10 pm. Lloyd & Yorath (Lloyd & Co.) must have bought the Rose in Hand to add to their small number of Forest of Dean pubs. Twelve years earlier in 1891 the pub was trading as a free house, with no brewery tie. E. Vaughan was the owner.

Gloucester Citizen: April 1880. Littledean Police Court. John Brain, landlord of the Rose in Hand, Morse Lane, near Ruardean, was summoned for permitting drunkenness, adjourned for a week on the application of Mr Whatley.

The Rose in Hand was featured in a ‘Citizen’ newspaper ‘Pubwatch’ review c.1999. Mother and daughter team Emma Fisher and Sally Smith were the new owners. At that time the Rose in Hand boasted three skittles teams – two ladies’, one men’s – plus league representation at darts and pool. The kitchen was in the process of being modified so that home-made meals and bar snacks could be served during the week. A small dining area with five or six tables was also planned. Sally told the ‘Citizen’, ‘Although we are making changes, we want the Rose in Hand to remain a local pub, and to retain a strong local atmosphere.’

A review in February 2006, following a Sunday visit by a family of three adults and two children, was quite complimentary: ‘The Rose in Hand is not on the main road and looks lost in time, but walk in and you’ll be welcomed by an open fire and friendly locals. On Sundays locals bring a dish of food- fried sweet potatoes, cheese and biscuits, sausages, crisps, onion bahjees – and you help yourself. You just put money in a box for a children’s charity.’ Of the pub food the reviewer wrote, ‘We went for a traditional roast. The food was delicious, large home-made portions and steamed vegetables. Sally the landlady even mashed-up beef and vegetables for my daughter, and pudding for her afterwards.’

An internet search for the Rose in Hand in May 2019 failed to get much up-to-date information. It has now been confirmed that the pub has closed, presumably permanently. When the Rose in Hand served its last pints apparently the beer was served from bottles only, the pub having no container beer.

Landlords at the Rose in Hand include:

1880,1885 John Brain

1891 William Griffiths

1902, 1906 Thomas Baldwin

1919 Mrs Edith Maud Garnsworthy

1927 Thomas H. Nicklen

1977-1997(approx.) Tony Ryan

1998 Sally Smith (formerly ran the Nelsons Arms)

I am very grateful to Jill Evans for her extensive research into the Rose in Hand at Drybrook which I have reproduced here: (c) 2018.

On Christmas night in 1889, the bar of the Rose in Hand was packed with revellers. The beer house, situated in Morse Lane, west of Drybrook, was frequented by miners who worked in the nearby pits, and was considered rather rough by the local authorities. On that night, just before ten o’clock, a local man, Joe Tyler, came into the bar and announced that he was going to sing a carol for the assembled company. However, the landlord told him that he was too late as the bar was about to close, so Tyler left without performing. About half an hour later, Tyler was found lying dead in a lane, about a quarter of a mile from the Rose in Hand. When the police arrived, they found several men waiting with the body, including twenty-three-year-old collier George Mansell. There were marks of violence on the deceased man’s head, and when witnesses stated that they had come across Mansell standing over the body, he soon found himself under arrest, on suspicion of murder.

Mansell appeared at Littledean Police Court on 27 December. It was stated that Joseph Tyler was a middle-aged, single man who worked as a stone-breaker for the County Council. He never had a bad word for anybody and was well liked by his neighbours, who considered him to be rather ‘simple’. On Christmas Day, he had been going about the local pubs singing carols. He had been in the Malt Shovel Inn at Ruardean before making his way to the Rose in Hand. After closing time, he was found lying dead in the road. He had a contused wound to the side of his head, which was likely to have been the cause of death. He had not been robbed, as there was money and a piece of cake in his pockets.

Some witnesses who lived near the lane where the deceased was found said that they heard the voices of men quarrelling, Mansell’s voice was recognised, and someone else was heard saying, ‘put that stone down’. It was believed that the wound on Tyler’s head had been made by a small stone from the road. Two women said they heard a man cry out several times, ‘Don’t George!’ The court was not satisfied that enough evidence had been gathered to charge Mansell, so the hearing was adjourned.

In the meantime, a Coroner’s Inquest opened on 28th December, at the National School, Drybrook. Superintendent Ford, of Coleford, gave evidence concerning the wound on Tyler’s forehead and of a stone being found twenty yards from where his body lay. It exactly fitted the wound on Tyler’s head and it had blood on it. Tyler’s walking stick was lying near to the stone. There were signs that someone had sat down next to where the stone was found. Regarding Mansell, there had been no blood or dirt on his clothing. The inquest was adjourned until 2 January 1890, when it re-opened at Drybrook.

More witnesses gave evidence on this occasion, including John Brain, the landlord of the Rose in Hand, who said he had stopped serving just as Tyler had come in. He believed Tyler had been sober. He cleared the house at quarter past ten. He saw Tyler go out with several others. He was not the last to leave. In reply to various questions from the coroner and inquest jury, he stated that the deceased did not ask for a drink, no-one had threatened the deceased, and no-one had said he must sing outside. The inquest was adjourned again until after the next court hearing at Littledean.

George Mansell next appeared at Littledean on 3 January 1890. This time, he had a barrister and a solicitor representing him. Superintendent Ford requested that the witnesses should be removed from the courtroom and brought in one by one, so they could not hear what the others said. Ford said he had had great difficulty obtaining any more information on the circumstances of Tyler’s death. However, a few new witnesses made an appearance.

First to give evidence was George Mansell’s younger brother, Richard. He thought that when he left the Rose in Hand on Christmas night, at about a quarter past ten, Joe Tyler had still been in the bar. He (Richard) parted company with George just outside the pub. Someone had asked him to take his brother home, but he didn’t, instead going to a friend’s house.

Thomas Evans, a collier from Ruardean Hill, said he had been at the inn on Christmas night. He had seen the deceased at the bar at closing time and had heard him singing outside just afterwards.

Thomas Williams said he went down the lane from the inn a bit after ten. He heard a voice say, ‘Get up Joe!’. There was no reply. Then he came upon George Mansell standing over Tyler’s body. Williams and Mansell both waited with the body until the police arrived. Mansell made no attempt to get away.

Timothy Marfell said he came across the scene and struck a light to see who the dead man was. George Mansell told him he had seen someone running away, so he went down the road to look, but only found a married couple walking home. Marfell waited with the others for the police to come. George Mansell had said to him, ‘This is a bad job’.

Moses Matthews said he was walking home when he came across a man standing over another and heard him say, ‘Get up Joe, the police will be here’.

Police Constable Seabright said he went to the prisoner’s house at two o’clock in the morning on December 26th. The prisoner was in bed. He denied knowing Tyler or seeing him the night before, until he came across his body. He though the man was drunk. He had dirt on his hands, which he said had been caused by dropping his pipe in the road. The pipe was examined and it did have dirt on it. Mansell lived with his parents and three sisters. He hadn’t told them what had happened, he said, because it was late when he got home and he didn’t want to wake them.

George Mansell swore that he was innocent of killing Joe Tyler. His defence lawyer said there was not enough evidence to commit the prisoner for trial and there was also no evidence of foul play, as Tyler might have fallen on the stone. Nevertheless, on 9 January 1890, Mansell was committed to Gloucester Gaol, to await trial at the next county Assizes.

The evidence against Mansell was slim, and he might have been given the benefit of the doubt, if he hadn’t already had a reputation for being a trouble-maker. In October 1889, he had been sentenced to 10 days in Littledean House of Correction, for assaulting Elijah Harrison without any provocation, knocking him insensible as he (the complainant) was walking into the Rose in Hand. In evidence, a police constable who knew Mansell said he was ‘a most quarrelsome fellow and created a row wherever he went’.

The Gloucestershire Assizes opened on 22 February 1890. Mr Justice Hawkins, in his opening address, summarized the case against George Mansell, and it was apparent that the judge had doubts about it, as he gave the jury pointers which he said might prove the prisoner innocent. These included that Tyler might have fallen on the stone, then staggered up the road before falling down dead. Regarding the question of why the prisoner had called the deceased ‘Joe’ when he stated that he did not know him, the prisoner had said he called every man he did not know by that name.

When brought into the dock, George Mansell looked around nervously, before pleading not guilty to the murder of Joseph Tyler on 25 December 1889. At this point, the prosecutor, Mr Sim, told the judge that his team felt that the evidence they had to call would only establish a case of grave suspicion against the prisoner. After a short consultation amongst the jury, the foreman announced that they agreed the case was not strong enough to proceed. His Lordship said this was the only sensible view to take, as it was far too serious a matter to put a man on trial for without strong evidence against him. George Mansell was discharged.

This was not the first time that the Rose in Hand had featured in a murder trial. The Gloucester Journal, in its report on the death of Joe Tyler, which appeared on 28 December 1889, stated that this was the same place where some years ago, ‘a poor fellow died from a stab wound inflicted in a public house known as the Rose in Hand, a beer-house in Morse Lane kept by a man named John Brain’. This incident took place in January 1876, when the landlord was not John Brain, but Frederick Bartlett.

Elijah Read, who was twenty years old, had tried to intervene in a fight between his brother Benjamin and a collier named Joseph Bidmead, which took place in the upstairs kitchen of the inn. When the fight broke up Read collapsed, clutching his belly, and it was discovered that he had been stabbed. Several other men who had been involved in the altercation found they had been cut too. Bidmead ran from the scene. Read was laid on the kitchen table, where he was attended by a doctor, who said there was little he could do, as the knife had gone into the bowels and perforated his intestines. He died two days later, on 19 January.

At the Gloucestershire Spring Assizes in April 1876, Bidmead was tried for the wilful murder of Elijah Reed. A verdict was returned of manslaughter, and Bidmead was sentenced to twenty years penal servitude. He was removed to Pentonville Prison on 5 May 1876.

Six months after the trial of George Mansell for the murder of Joe Tyler, The Citizen newspaper (23 Aug 1890) reported that John Brain, landlord of the Rose in Hand alehouse, Morse Lane, Drybrook, had been fined for permitting drunkeness on his premises on two occasions. The newspaper commented: ‘This house has been badly conducted for a long time. Two persons have been committed for trial for murder since February 1876. These “murders” originated among persons who had been drinking on these premises. One occurred on 25 December last. This licence has since been transferred from Mr Brain to another person.’

Despite its troubles in the late nineteenth century, the Rose in Hand continues as a public house to this day.

Sources

Gloucester Journal, 29 Jan 1876, 28 Dec 1889, 4 Jan 1890

Gloucester Citizen, 19 Oct, 30 Dec 1889, 23 Aug 1890

Gloucestershire Chronicle, 1 March 1890

Wiltshire and Gloucestershire Standard, 15 Apr 1876

Gloucestershire Prison Records (viewed on Ancestry.co.uk. Originals at Gloucestershire Archives):

Littledean House of Correction, Registers of Prisoners, 1881-93

Gloucester County Gaol, Nominal Prisoners Registers, 1889-90

Illustration from geograph.org.uk.

© Jill Evans, 2018